Rewriting Yusuf

A Philological and Intertextual Study of a Swahili Islamic Manuscript Poem

von Annachiara Raia, Vorwort von Farouk TopanThis work centres on a long narrative poem, the ‘Utendi wa Yusufu’. This is the Swahili version of the story of Joseph, son of Jacob, as he is called in the Old Testament, or the Arabic Yūsuf ibn Ya‘qūb, revered by both Judeo-Christian and Muslim communities. The story has been disseminated all over the world, translated into many different languages and adapted into various genres throughout the centuries, making it one of the most widely-travelled stories of mankind. The story also made its way to the East African coast and became widespread at the beginning of the twentieth century and probably even in the nineteenth. In the context of this work, I will focus on the earliest surviving East African versions of the story that we have, which have been preserved in manuscripts in Arabic script.

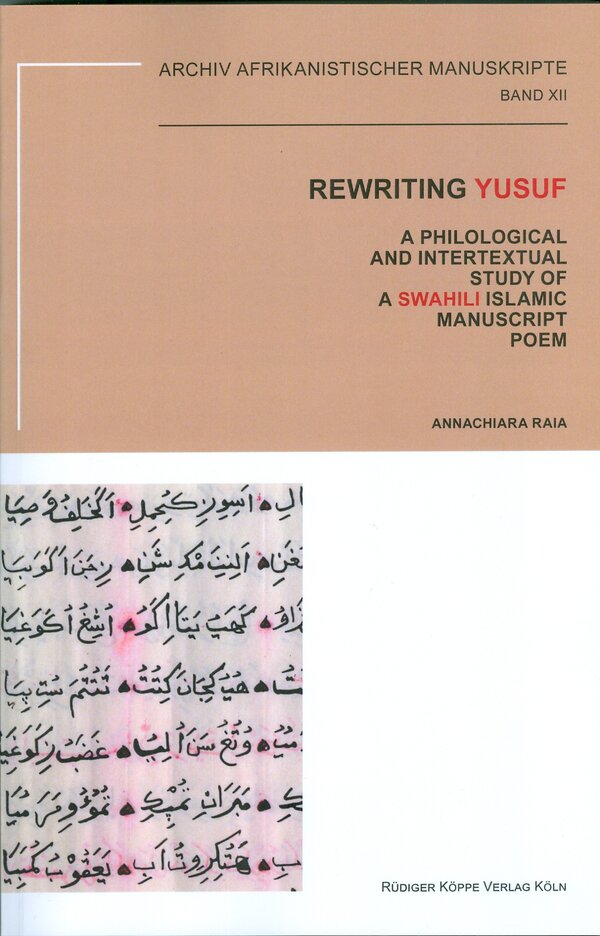

In its core, the present study offers the textual history, critical edition and translation of the ‘Utendi wa Yusufu’. The poem has been circulated in several manuscripts in Arabic script. Although I will give an overview of all the manuscript versions available, my text edition is based on three manuscripts penned by two different scribes. The manuscripts have never been transliterated, commented on or translated – my work is the first critical text edition of the poem.

The second aim of this monograph is to consider the aspect of adaptation: how is the story, which has been so widely circulated, re-narrated in East Africa and from a Swahili coastal perspective? How did it become part of Swahili intellectual history? How did the Swahili poet transform the text to make it his own? How does the Swahili text differ from the presumably similar text of the Qur’ān or the Qiṣaṣ? Since the story has been so popular and widely diffused throughout the whole area of the Indian Ocean, and translated and adapted over centuries and across continents, the Swahili ‘Hadithi ya Yusufu’ then makes for a riveting case study of appropriation: it is a specific text in a relatively well-known genre, the utendi, which can tell us more about the ‘Swahili’ form of ‘translating’ ‘foreign’ stories into local context. This study of appropriation is text-oriented and has concentrated on two principal intertextual sources of the ‘Utendi wa Yusufu’, which are both part of Islamic tradition but pertain to two different genres: firstly, the Holy Qur’ān, and more specifically, the ‘Sūrat Yūsuf’, and secondly, the Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyā’, a widely-known cycle of literature about the prophets who lived prior to Muhammad.

There have been a number of hints at the intertextual links between the Swahili poem of the ‘Utendi wa Yusufu’ and these Arabic sources. However, my study makes the first attempt to thoroughly examine the interrelationship between the Swahili poem and the two texts. As I will show, focusing on the comparison, the Swahili text differs from both texts quite substantially, both with respect to the presence and absence of motifs, as well as the depiction of the story and its style. Both the liberty that the poet takes in amplifying the text, but also the utendi’s style, its epic length and its episodic structure have a decisive bearing on the story. Finally, I will also consider the implications of the specific modes of adaptation found in the utendi. What do they reveal about the poet’s attitude towards the text?

*** Die Autorin behandelt in ihrer hier vorgelegten und für die Veröffentlichung überarbeiteten Dissertation eine kritische Textedition der Josefsgeschichte und eine Studie zu ihrer Adaption an der Swahili-Küste Ostafrikas.

Die Geschichte von Joseph wurde auf der ganzen Welt verbreitet, in viele verschiedene Sprachen übersetzt, und im Laufe der Jahrhunderte in verschiedene Genres adaptiert, was sie zu einer der am weitesten verbreiteten Geschichten der Menschheit macht. Der jugendliche Kanaaniter Joseph, Sohn Jakobs, wie er im Alten Testament genannt wird – Yūsuf ibn Yaʿqūb auf Arabisch – ist eine Figur, die sowohl von jüdisch-christlichen als auch von muslimischen Gemeinschaften verehrt wird. Yusuf war Yaqubs elfter Sohn, und am meisten von seinem Vater geschätzt; sein Vater hielt sich nie zurück, seine Bevorzugung für seinen geliebten und längst verlorenen Sohn zu zeigen. Er wurde in Paddan-Aram von der gerechtesten und schönsten Frau von Yaqub, Rachel, geboren, nachdem sie sieben Jahre lang unfruchtbar gewesen war. Seine Schönheit ist legendär und Gegenstand vieler apokryphischer Darstellungen): Gott hat ihm zwei Drittel aller menschlichen Schönheit zugeteilt.

Seine Geschichte geht auf das 5. Jahrhundert v. Chr. – während des jüdischen Exodus aus Ägypten – zurück, und findet im Kontext verschiedener multiethnischer und kosmopolitischer Königshöfe statt: dem pharaonischen, assyrischen, babylonischen und persischen, sowie dem achämenidischen und hellenistischen. Als solche werden die Geschichten von Josephs Standhaftigkeit, seiner Liebe zu seinem Vater Yaqub, seiner Loyalität zu seiner Familie und seinem Verhalten im hohen pharaonischen Amt inmitten einer Reihe von Ereignissen erzählt – einschließlich eines schweren Hungerzyklus’, der auf die siebenjährige Trockenheit des Nils zurückzuführen ist – in der Regierungszeit des Königs Djoser aus der 3. Dynastie (ca. 28. Jahrhundert v. Chr.). Diese führte schließlich zum jüdischen „Exil“ und zur Migration nach Ägypten, ihrer Versklavung und Erlösung.

Wie auch Aufzeichnungen über den Handelsverkehr von Menschen zwischen Kanaan und Ägypten ab dem 18. Jahrhundert v. Chr. dokumentieren, wurde Joseph als Sklave in Ägypten verkauft. Die Siedlung, in der er verkauft wurde, heißt Tel Dothan. Die verschiedenen Titel und Funktionen, die ihm der ägyptische Pharao verliehen hat, sprechen von einem bekannten Merkmal der damaligen ägyptischen Bürokratie.

Joseph starb im Alter von 110 Jahren – von den Ägyptern als das ideale Alter angesehen. Er erfüllte den sterbenden Wunsch seines Vaters, der im Ahnengewölbe in Kanaan beigesetzt war, aber nach seiner Beerdigung nach Ägypten zurückgebracht wurde. Als Joseph starb, soll er in Ägypten einbalsamiert und in einen Sarg gelegt worden sein, ein Ritual, das Joseph mit der in Ägypten weit verbreiteten Tradition der Mumifizierung von Körpern zu verbinden scheint.

In its core, the present study offers the textual history, critical edition and translation of the ‘Utendi wa Yusufu’. The poem has been circulated in several manuscripts in Arabic script. Although I will give an overview of all the manuscript versions available, my text edition is based on three manuscripts penned by two different scribes. The manuscripts have never been transliterated, commented on or translated – my work is the first critical text edition of the poem.

The second aim of this monograph is to consider the aspect of adaptation: how is the story, which has been so widely circulated, re-narrated in East Africa and from a Swahili coastal perspective? How did it become part of Swahili intellectual history? How did the Swahili poet transform the text to make it his own? How does the Swahili text differ from the presumably similar text of the Qur’ān or the Qiṣaṣ? Since the story has been so popular and widely diffused throughout the whole area of the Indian Ocean, and translated and adapted over centuries and across continents, the Swahili ‘Hadithi ya Yusufu’ then makes for a riveting case study of appropriation: it is a specific text in a relatively well-known genre, the utendi, which can tell us more about the ‘Swahili’ form of ‘translating’ ‘foreign’ stories into local context. This study of appropriation is text-oriented and has concentrated on two principal intertextual sources of the ‘Utendi wa Yusufu’, which are both part of Islamic tradition but pertain to two different genres: firstly, the Holy Qur’ān, and more specifically, the ‘Sūrat Yūsuf’, and secondly, the Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyā’, a widely-known cycle of literature about the prophets who lived prior to Muhammad.

There have been a number of hints at the intertextual links between the Swahili poem of the ‘Utendi wa Yusufu’ and these Arabic sources. However, my study makes the first attempt to thoroughly examine the interrelationship between the Swahili poem and the two texts. As I will show, focusing on the comparison, the Swahili text differs from both texts quite substantially, both with respect to the presence and absence of motifs, as well as the depiction of the story and its style. Both the liberty that the poet takes in amplifying the text, but also the utendi’s style, its epic length and its episodic structure have a decisive bearing on the story. Finally, I will also consider the implications of the specific modes of adaptation found in the utendi. What do they reveal about the poet’s attitude towards the text?

*** Die Autorin behandelt in ihrer hier vorgelegten und für die Veröffentlichung überarbeiteten Dissertation eine kritische Textedition der Josefsgeschichte und eine Studie zu ihrer Adaption an der Swahili-Küste Ostafrikas.

Die Geschichte von Joseph wurde auf der ganzen Welt verbreitet, in viele verschiedene Sprachen übersetzt, und im Laufe der Jahrhunderte in verschiedene Genres adaptiert, was sie zu einer der am weitesten verbreiteten Geschichten der Menschheit macht. Der jugendliche Kanaaniter Joseph, Sohn Jakobs, wie er im Alten Testament genannt wird – Yūsuf ibn Yaʿqūb auf Arabisch – ist eine Figur, die sowohl von jüdisch-christlichen als auch von muslimischen Gemeinschaften verehrt wird. Yusuf war Yaqubs elfter Sohn, und am meisten von seinem Vater geschätzt; sein Vater hielt sich nie zurück, seine Bevorzugung für seinen geliebten und längst verlorenen Sohn zu zeigen. Er wurde in Paddan-Aram von der gerechtesten und schönsten Frau von Yaqub, Rachel, geboren, nachdem sie sieben Jahre lang unfruchtbar gewesen war. Seine Schönheit ist legendär und Gegenstand vieler apokryphischer Darstellungen): Gott hat ihm zwei Drittel aller menschlichen Schönheit zugeteilt.

Seine Geschichte geht auf das 5. Jahrhundert v. Chr. – während des jüdischen Exodus aus Ägypten – zurück, und findet im Kontext verschiedener multiethnischer und kosmopolitischer Königshöfe statt: dem pharaonischen, assyrischen, babylonischen und persischen, sowie dem achämenidischen und hellenistischen. Als solche werden die Geschichten von Josephs Standhaftigkeit, seiner Liebe zu seinem Vater Yaqub, seiner Loyalität zu seiner Familie und seinem Verhalten im hohen pharaonischen Amt inmitten einer Reihe von Ereignissen erzählt – einschließlich eines schweren Hungerzyklus’, der auf die siebenjährige Trockenheit des Nils zurückzuführen ist – in der Regierungszeit des Königs Djoser aus der 3. Dynastie (ca. 28. Jahrhundert v. Chr.). Diese führte schließlich zum jüdischen „Exil“ und zur Migration nach Ägypten, ihrer Versklavung und Erlösung.

Wie auch Aufzeichnungen über den Handelsverkehr von Menschen zwischen Kanaan und Ägypten ab dem 18. Jahrhundert v. Chr. dokumentieren, wurde Joseph als Sklave in Ägypten verkauft. Die Siedlung, in der er verkauft wurde, heißt Tel Dothan. Die verschiedenen Titel und Funktionen, die ihm der ägyptische Pharao verliehen hat, sprechen von einem bekannten Merkmal der damaligen ägyptischen Bürokratie.

Joseph starb im Alter von 110 Jahren – von den Ägyptern als das ideale Alter angesehen. Er erfüllte den sterbenden Wunsch seines Vaters, der im Ahnengewölbe in Kanaan beigesetzt war, aber nach seiner Beerdigung nach Ägypten zurückgebracht wurde. Als Joseph starb, soll er in Ägypten einbalsamiert und in einen Sarg gelegt worden sein, ein Ritual, das Joseph mit der in Ägypten weit verbreiteten Tradition der Mumifizierung von Körpern zu verbinden scheint.