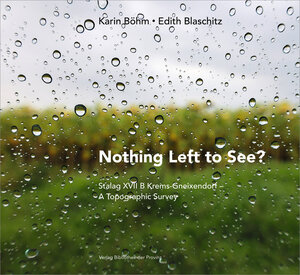

Nothing Left to See?

Stalag XVII B Krems-Gneixendorf – A Topographic Survey

von Karin Böhm und Edith Blaschitz, aus dem Deutschen übersetzt von Tim CorbettThe largest Prisoner of War (POW) camp of World War Two on the territory of present-day Austria was located near the village of Gneixendorf outside the City of Krems: Stalag XVII B Krems-Gneixendorf. At certain times, there were as many as 60,000 POWs of various nationalities interned here. There is hardly anything left to see of it today. The site is occupied by an airfield with restaurant adjacent, crisscrossing roads, forests, meadows, and fields. Some remains of the foundations of the military personnel barracks are preserved on the overgrown terrain near the airfield, as well as further east a massive water reservoir. The steel plaques of an art installation and a few weathered memorial stones refer to the history of the site.

For two and a half years, the photographer and photo journalist Karin Böhm repeatedly visited the site of about a square kilometer, which lies close to her home. When choosing her route, she let herself be guided on a journey of chance discovery by her interests, knowledge, and intuition. Her perseverant engagements with the site resulted in a photographic observation and survey. Karin Böhm found relics of the past, abandonment to overgrown nature, as well as contemporary usages of the site and plotted these using geo-coordinates.

Parallel to her work, the historian and cultural studies scholar Edith Blaschitz researched historical sources pertaining to Stalag XVII B in the framework of the research project “NS-‘Volksgemeinschaft’ und Lager im Zentralraum Niederösterreich. Geschichte – Transformation – Erinnerung” (The Nazi ‘Volksgemeinschaft’ and Camps in the Center of Lower Austria: History, Transformation, and Memory). This research revealed new insights on the French POWs, the largest national prisoner group, as well as the hitherto under-researched Belgian, Italian, Serbian, and Spanish POWs. The perspectives of the internees, their contacts with the local population, and engagements with the memory of the camp formed the focal point of this research project, which also included interviews and correspondence with the few surviving eyewitnesses as well as descendants of the POWs, the camp personnel, and local residents of the surrounding towns.

Karin Böhm wove her survey of the present-day site together with the historical documents and current reactions emerging from the research project – photographs, drawings, letters, emails, interviews, diary entries, maps, and documentation – to create a dense visualtextual ensemble. Four chapters, beginning with quotes and personal notes, are dedicated to the POWs, their deployment for labor, the camp personnel, and the search of descendants. Historical and present-day photographs are placed in dialogue with one another and thus open up new levels of observation. The connection between past and present is not only visible in the photographically documented traces of the historical site, but also in the reproductions of historical documents marked with ‘traces’ of the present – a yellowed photograph in the hands of its owner, a table in the archive.

Karin Böhm and Edith Blaschitz repeatedly enquire into the connection between a site that today appears to be ‘empty,’ yet remains anchored in the memories of many families worldwide, and the past. Together, they reflect upon the meanings evoked against the background of historical events. The juxtapositions, where necessary, were adapted.

Karin Böhm’s photographs sometimes require a second look in order to perceive details, following which ostensibly idyllic images crumble. Selected aspects of this complex artistic “visual-textual-mosaic” are analyzed by the art historian and visual scholar Viola Rühse in the concluding essay, which pays special attention to the present-day images.